Cure Your depression? Take a Trip, Man!

I could not believe it when the patient asked me about ketamine. I had just seen an episode of “House, MD” on one of those cable super-stations the night before and it dealt with this weird drug. I told my husband about my experiences with it during my surgical career. Then, the next day, this patient brought up the same rare drug. When I looked at him closer, it became believable. He was old enough — in his sixties — that in the swinging sixties he had surely been one of those “knowledgeable” druggies who pride themselves on knowing all about everything that could give one a buzz.

This type of person is a sort of lay-pharmacologist — someone who knows not only how each drug made someone feel, but sometimes even about class of drug and mechanism of action. Of course, this type of expert would seldom know terribly much about what the FDA thought or felt about these drugs. “I heard it works pretty well and faster than anything on depression,” he said, “and I am kind of depressed and the standard antidepressants, the crap like Prozac and Zoloft aren’t worth taking and don’t do anything. But they say that stuff works fast on depression.”

Yes, he knew his stuff so well that he may even have read some kind of FDA reports or something. Still, ketamine is not the kind of thing you can dish out in a county clinic in Noplace, California. If you want something exotic, try a university psychiatry or pharmacology department, or call or email the National Institutes of Health. I could offer the standard stuff, but not ketamine. Not me, not there.

Of course, the patient did not want the “standard stuff” from me or anybody. He told me he was not psychotic and would never kill himself or anyone else — for clearly this was a man who knew the drill — and so he ran from the office, probably to phone the NIH or a university in Los Angeles or San Francisco.

It had been a long time since I had looked at the literature of ketamine — which is fascinating. The report that the patient was alluding to was a 2006 study by Carlos Zarate, Jr. MD where he gave some ketamine to people who had treatment-resistant depression and — after a single dose — people had improvements in their depression that lasted over a week. (According to Archives of General Psychiatry 2006,63:856-864)

In a field where medications are patiently taken daily for a good month before the effects come, this is unprecedented. Ketamine was originally supposed to be used as an anesthetic — animal and human. Since it had the wonderful property of diminishing consciousness without diminishing cardiac or respiratory functions, in theory — at least — it would make a great anesthetic for use in the field, where a surgeon could operate alone with no more than a passing glance at vital signs.

Its use in Vietnam was followed by reports from Veterans who had been operated upon that they had some pretty psychedelic experiences while they were under. Of course, people often have unusual experiences under anesthesia and it is not unusual for drugs to do different things at different concentrations, but ketamine has a lot of powers and a lot of surprises. Chemically, ketamine is an arylcyclohexylamine which means that it is related to dextromethorphan, or DXM, (Yes, the stuff in cough syrup) — known in some circles as “robo” — and PCP, otherwise known on the street as “angel dust.”

I do have a personal anecdote for the one and only time I actually dealt with a patient who had taken angel dust. He was a large, muscular pumped-up soldier who grabbed me in his arms and was yelling and screaming all sorts of unintelligible things.

I, on the other hand, was screaming at the top of my lungs, “Ten mg. of Haldol IM now, nurse! Anyplace — his shoulder, his buttock, anything! Help!” Happy ending – the nurse’s aim was true and she nailed him in the buttock. I felt that my prayers were answered. Fortunately, I had read in a medical journal not long before this was what you were supposed to do with someone on PCP. I know they called for security and my feet did indeed find the floor, giving me sense of relief unparalleled in my lifetime. I mean, I always thought of that moment as the closest I had ever gotten to combat, for I happened to be in the U.S. Army medical corps uniform at the time. So believe me, nobody has to convince me that this drug must be an hallucinogen.

I know it is great for pain — all kinds of pain of dramatic and overwhelming intensity, like CPRS or Complex regional pain syndrome, and there is even some local trans-dermal kind of use.

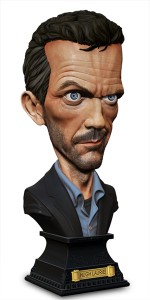

That was part of the plot of “House MD” referenced at the beginning of this post. The good doctor has a chronically bum leg and Vicodin habit from the pain. After he undergoes surgery because of an assault by an irate patient, and was subjected to ketamine as a surgical anesthetic, he awakens pain-free for the first time in years. But his brain plays tricks on him and he seems to be hallucinating. He is angry, since he would rather have a painful leg and all of his faculties.

Real-life is more controversial than network TV, and ketamine is being actively researched in the Near East and in the former Soviet Union, exploring the notion that ketamine may be helpful for pychotherapy. One of the first things learned in psychotherapy is the importance of the abreaction, the sort of reliving of the central stressful painful story in someone’s life so that it is somehow, in the imagination, made correct, and the person made better. It is claimed that ketamine may be helpful in such circumstances. A related chemical, ibogaine, has been used in these ways for addictions, traumas, and all of the like. It seems a British group has used ketamine with dramatically positive results on anorexia nervosa and obsessive compulsive disorder. Now although obsessive compulsive disorder seems to be so common it may effect as much as 3% of the population, it has been long recognized that there are some cases so severe that they justify a surgical approach.

I was actually involved in one case in France, when I was still a neurosurgeon in training, where a frontal cingulotomy — first of one hemisphere and then the other — failed to help a young man stop obsessing over his clothes and putting them on, to such an extent that his parents spent the whole day helping him dress, and ignored the family farm to such an extent that they finally lost it. Ketamine and other psychedelic drugs do not seem to be a fast answer to addictions and psychiatric diagnoses in situations that seem particularly difficult to treat. It seems to take more than one injection, and the variability of doses for the different applications … well this is complex stuff. People are actively researching.

Some problems have been advanced not just by looking at natural substances, but by looking at alternative uses for substances that are prescriptions that we already know. The only thing that is for sure is that we are not yet in a situation where this stuff can be dished out at a county mental health center in what some might call the agrarian part of California.

Filed under depression by on Dec 24th, 2010. ![]()

Leave a Comment