The Operation Was A Success, But The Patient Died

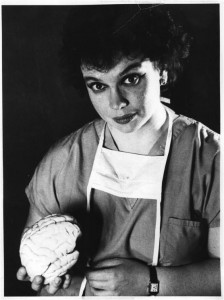

She was a young female staffer in her first professional position. What she may have lacked in experience, she made up for with a lot of heart and she extended her maximum effort for every single patient.

I had been like that in the beginning, too. At first, you have no body of knowledge to draw upon, but you quickly learn every time a new patient comes in. With experience, you see it becomes clear patients are more alike than different, and the work is at least a little less onerous.

But our newbie had a very few months experience with this intense clinical situation. So every single patient was new and scary, and she gave her all. One week before she had dealt with one of the most difficult situations.

A young man had admitted to some thoughts of suicide. But he said he had worked them through, so that they were no longer in his thoughts, and he gave the classical (and much sought) “contract for safety.” Often oral and sometimes, when somebody wants or needs something concrete, written, it is a promise to live. A promise that covers the institution and individual working with such a person for legal reasons and says “we thought of this.”

He had been living in the park, he claimed, but sometimes with “friends;” he had told us a lot of things we couldn’t trace. In public health clinics, you often see people of similar situations. Even our new staffer had encountered patients like this before.

All you can do is document, I counseled her. All any supervisor will ever say is “document, document, document.”

It was one week later and he had returned. Razor blade marks on his forearms. Fresh, yes, but on the wrong side of his forearm. Not on the side where most if not all of the blood vessels of the forearm were located. It was lack of knowledge of anatomy that had kept him living. The decorated if not destroyed forearm was in the arm of—his mother. We assumed she had thrown him out long ago; that is not at all uncommon.

He would go to another staff member now, as our new staffer was hurt; it was clear. She was fighting tears, as if she did not want me to see, but she had always been open with me. I loved her as I loved those in whom I saw a little of myself, however small the sliver.

“I feel terrible. I feel I did wrong or did bad or something. I failed him.”

I took a long sigh. I told her a little about one of my earliest psychiatric patients, and my own evolution. It was western Canada, and I had just switched over to psychiatry from neurosurgery, so the clinical professors assumed that I was pretty much useless. They were mostly right.

Me, I was as obsessive about knowledge as I had ever been, so when I was assigned my first inpatient — just one — they told me to spend as much time with her as I could, and learn all I could from her.

She was about my age, and was married to a man who had treated her quite poorly — coming home drunk, raping and beating and such. She had been admitted because she was suicidal. She had given her kids to her sister, who had been all too happy to “spell” her from her responsibilities for a bit. She had taken pills, and lots of them, and had been through the ritual cleaning of the stomach before she had a chance to tell me her tale of woe.

I had been up for the greater part of three nights, reading all about suicidality and about women victimized in such situations. By the time I dismissed her, she was properly medicated, asymptomatic, smiling, with a list of shelters and a personal therapist (paid for back then, by the Canadian National Health Service).

I felt that I had done very well. I even sent her home with just one week’s worth of medication, so she could not have used the pills to kill herself even had she wanted to. Yeah, I did good.

Less than a week later, she returned — this time with cuts on her wrists. On the correct side of the forearm. The wounds had been dutifully sutured by someone, probably a medical student or intern, in the emergency room.

She felt bad that the cuts had not been more effective. I felt bad that all of the work I had done had been not only not helpful, but had led to this.

Of course I called my preceptor right away. Although he was “in charge” of me, I did not know him terribly well, except that he was trained as an analyst and had a (barely) little knowledge about pharmacology. He was a typical middle-aged doctor-type and you’ve seen his character portrayed on TV and movies.

He wasn’t exactly touchy-feely, and had never had much eye contact with me, even when we spoke. So I was surprised when he offered to buy me a coffee in the cafeteria.

I admit I was feeling pain. I mean, I was now questioning if I’d made the correct decision in changing from neurosurgery? If this is how you tell, I could be in trouble.

I did not speak the level of insecurity I felt as I sat down with him in the cafeteria. “Didn’t you used to be a surgeon?” he asked me.

Obviously, I could only answer “Yes.”

“Didn’t you ever have times when the operation was a success but the patient died?”

Again, I could only answer “Yes.”

“Well that is what has happened here.” He went on a bit, but already I felt as if an anvil had been lifted off my shoulders. “You did everything right. No — better than right. Excellently.”

He was right. I had read everything I could find on the subject, reported to him all the things I had said and did.

“She made some very bad choices. She chose not to follow your directions, not to go through with what you had planned for her. A very bad choice.”

He was right. She had made mad choices. It was not my fault. I could not have made her choices for her.

He was still babbling a bit when I interrupted him to tell him that the intervention he had made with me, telling me that, had been wonderful and brilliant.

“No big deal,” he said, for someone had told him something like that once, when he had been a beginner. And he loved teaching, so it was his time to tell it to me, and that was great. He even winked, and admitted that it had made him feel better to hear such things, long ago, but that everything gets easier with time and experiences.

So years later, in rural agricultural California, I told a devoted young female staffer the above story and she looked away from my face. Her tears were gone, and she smiled, and she said “That was great. That really made me feel a lot better. Thank you.” She gave me as sincere a hug as I have ever received from anyone.

I hope she passes that wisdom on someday when she is the supervisor. In fact, I’m certain she will.

Filed under End Of Life by on Jan 18th, 2011. ![]()

Leave a Comment